Copypasta

noun

A block of text that is duplicated repeatedly via "copy-paste",

often causing annoyance or frustration.

One the the biggest problems (if not the biggest problem) I have seen in test automation is copypasta – the unnecessary duplication of code. It happens at all layers of testing. It happens in any type of project. It happens at companies big and small. And the consequences are stark: test development slows down, mistakes become more common, and maintenance becomes a nightmare. Although duplicate code can happen in any software project, it is especially prevalent in test automation. The reasons may or may not surprise you, but the solutions are clear.

4 Reasons Why Duplicate Code Pervades Automation

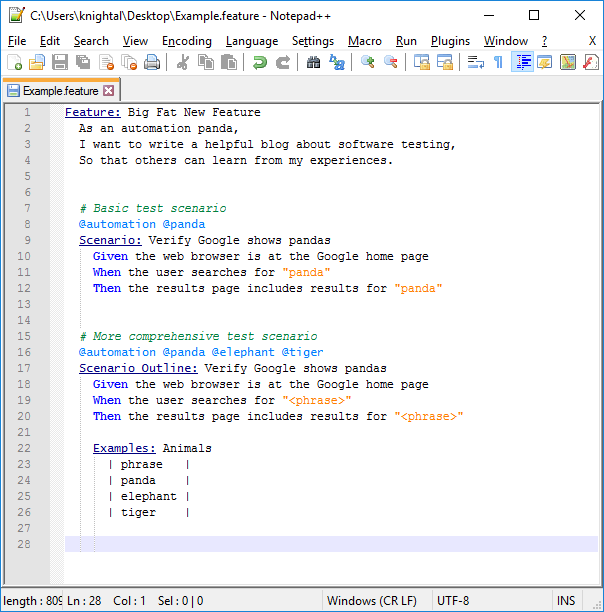

#1: Test cases are repetitive. For any given product, tests will share many of the same steps. For example, web app tests must all navigate to a start page at first, or API tests might cover a few variations for one call. Testing mechanics such as input parameters, setup/cleanup, logging, and assertions happen frequently. Put all of that together into test suites that have tens, hundreds, thousands, or even more test cases. It’s simply the nature of testing.

#2: Automation frameworks reinforce repetition. Most frameworks structure test cases as a class with methods (like JUnit) or as a collection of functions (like pytest), in which each method or function represents one test. Inherently, this basic structure is a good thing for making tests independent. However, lazy programmers may abuse the structure. Often, they put all test code inside these test methods, instead of extracting repetitive logic into helper methods or design patterns. Then, it becomes easier to simply duplicate an entire test case method and change a few things, rather than to implement a better overall design.

#3: Test code takes a backseat to product code. Business needs drive software development in the industry, and since test code is not part of the product delivered to customers, it is often deemed to be less important. Not as much devotion is given to developing good test code. Many best practices are abandoned for expediency.

#4: Testers often have weaker development skills. This is not a condemnation of testers, nor a universal labeling, but rather a distinction between disciplines: developers are developers because they are good at making software, and testers are testers because they are good at exercising software and finding bugs. Of course, I know plenty of testers who do indeed have strong dev skills. However, I also know solid testers who have limited programming experience. When automation responsibility falls upon testers with limited dev skills, poor development practices happen, and code duplication is typically rampant.

How to Avoid Duplicate Code in Automation

Code duplication is code cancer. -Andy

There are a number of ways to slay the copypasta monster. The first line of defense is to check yourself before you wreck yourself. Always question yourself when you copy-paste blocks of code. Why did you do that? What are you changing in the pasted copy? Should you abstract that logic into a method or a class that can be reused? Can you parameterize it? Override your Ctrl-C, Ctrl-V keyboard shortcut if necessary.

Be a good programmer. Develop packages for reusable actions. Things like assertions, logging, setup, and cleanup should be shared by all test cases. In that shared code, keep action calls short. Long method names with too many parameters inhibit usability. Remember that automated test cases should be self-documenting so that they read like test procedures. Whenever possible, make repetitive actions happen automatically. For example, make library methods do internal logging, and use test framework setup/cleanup routines. For another example, I once wrote code to automatically reconnect SSH sessions whenever they dropped. These auto-actions allow test case code to focus less on the low-level mechanics and more on the high-level features under test.

Finally, be a team player. Use the same development practices for test code as for product code. Automation is a product, and its customers are the team. Use coding standards, design patterns, and revision control. Most importantly, reinforce good practices through code review. Use the review process as a constructive way to learn new tricks and even to mentor less experienced team members. Finally, divide testing roles between test formulation, test case automation, and test framework development. “QA” (quality assurance) is a wide discipline, and not everyone is equally skilled. Let people do what they do best. There is strength in diversity and in teamwork.