This article is based on my talk at PyCon US 2023. The web app under test and most of the example code is written in Python, but the information presented is applicable to any stack.

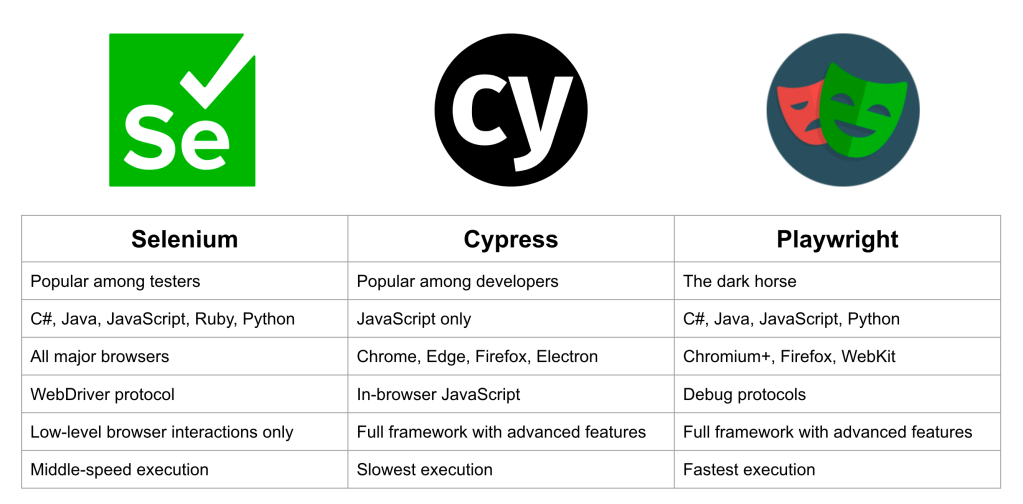

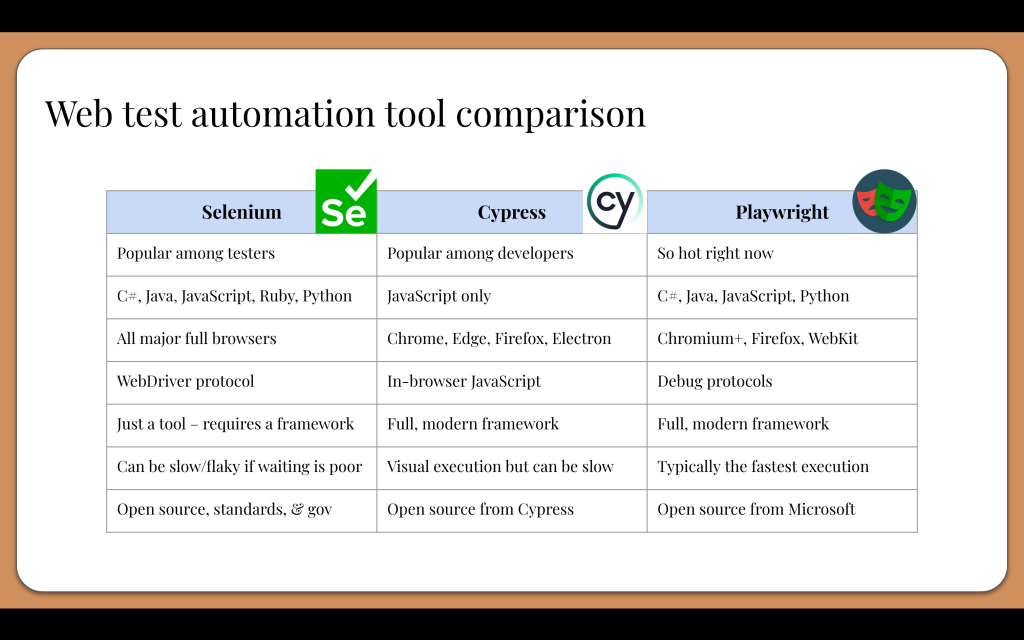

There are several great tools and frameworks for automating browser-based web UI testing these days. Personally, I gravitate towards open source projects that require coding skills to use, rather than low-code/no-code automation tools. The big three browser automation tools right now are Selenium, Cypress, and Playwright. There are other great tools, too, but these three seem to be the ones everyone is talking about the most.

It can be tough to pick right right tool for your needs. In this article, let’s compare and contrast these tools.

Choosing a web app to test

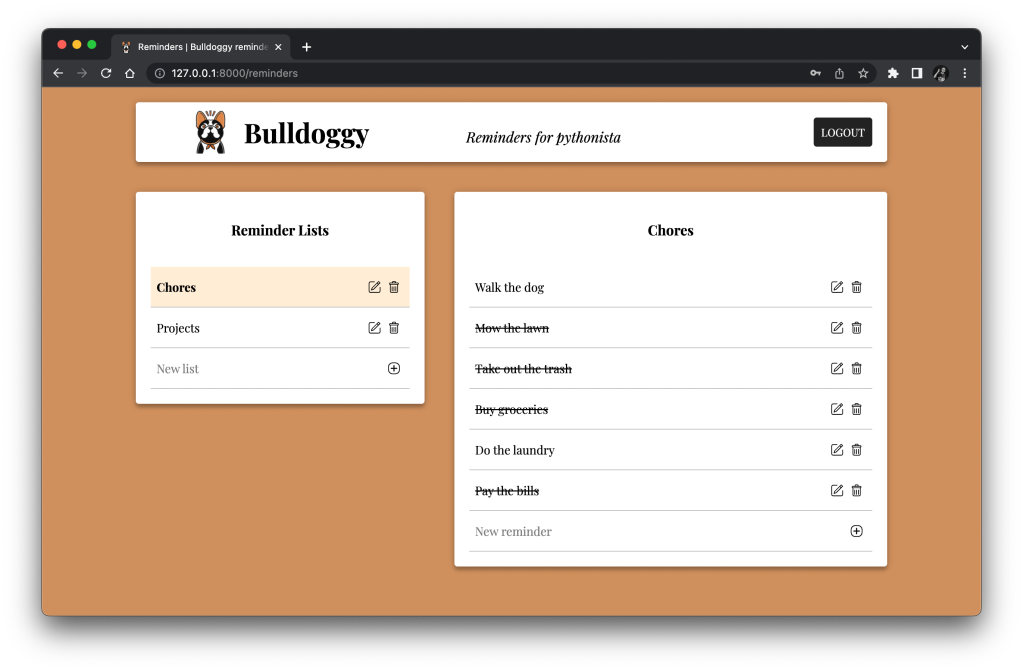

I developed a small web app named Bulldoggy, the reminders app. You can clone the repository and run it yourself. The repository URL is https://github.com/AutomationPanda/bulldoggy-reminders-app.

Bulldoggy is a full-stack Python app:

- It uses FastAPI for APIs.

- It uses Jinja templates for HTML and CSS files.

- It uses HTMX for handling dynamic interactions without needing any explicit JavaScript.

- It uses TinyDB to store data.

- It uses Pydantic to model data.

If you want to run it locally, all you need is Python!

The app is pretty simple. When you first load it, it presents a standard login page. I actually used ChatGPT to help me write the HTML and CSS:

After logging in, you’ll see the reminders page:

The title card at the top has the app’s name, the logo, and a logout button. On the left, there is a card for reminder lists. Here, I have different lists for Chores and Projects. On the right, there is a card for all the reminders in the selected list. So, when I click the Chores list, I see reminders like “Buy groceries” and “Walk the dog.” I can click individual reminder rows to strike them out, indicating that they are complete. I can also add, edit, or delete reminders and lists through the buttons along the right sides of the cards.

Now that we have a web app to test, let’s learn how to use the big three web testing tools to automate tests for it.

Selenium

Selenium WebDriver is the classic and still the most popular browser automation tool. It’s the original. It carries that old-school style and swagger. Selenium manipulates the browser using the WebDriver protocol, a W3C Recommendation that all major browsers have adopted. The Selenium project is fully open source. It relies on open standards, and it is run by community volunteers according to open governance policies. Selenium WebDriver offers language bindings for Java, JavaScript, C#, and – my favorite language – Python.

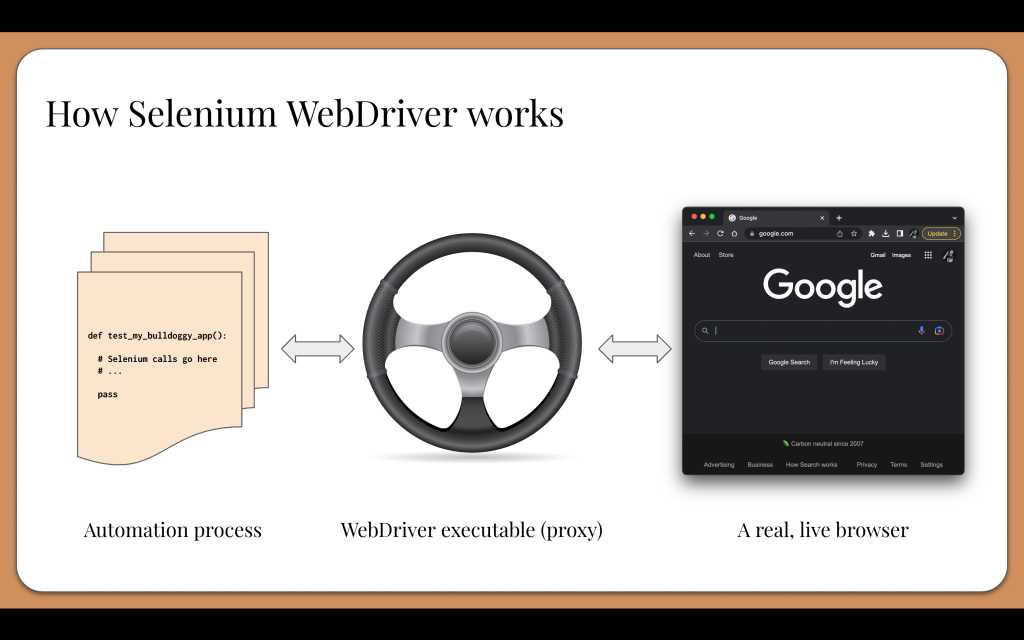

Selenium WebDriver works with real, live browsers through a proxy server running on the same machine as the target browser. When test automation starts, it will launch the WebDriver executable for the proxy and then send commands through it via the WebDriver protocol.

To set up Selenium WebDriver, you need to install the WebDriver executables on your machine’s system path for the browsers you intend to test. Make sure the versions all match!

Then, you’ll need to add the appropriate Selenium package(s) to your test automation project. The names for the packages and the methods for installation are different for each language. For example, in Python, you’ll probably run pip install selenium.

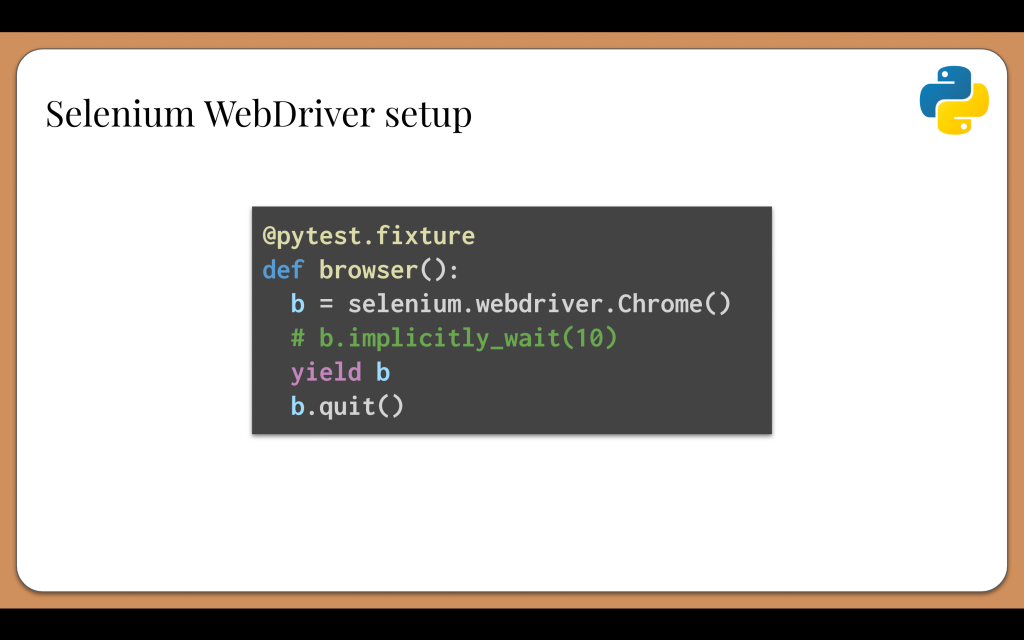

In your project, you’ll need to construct a WebDriver instance. The best place to do that is in a setup method within a test framework. If you are using Python with pytest, that would go into a fixture like this:

We could hardcode the browser type we want to use as shown here in the example, or we could dynamically pick the browser type based on some sort of test inputs. We may also set options on the WebDriver instance, such as running it headless or setting an implicit wait. For cleanup after the yield command, we need to explicitly quit the browser.

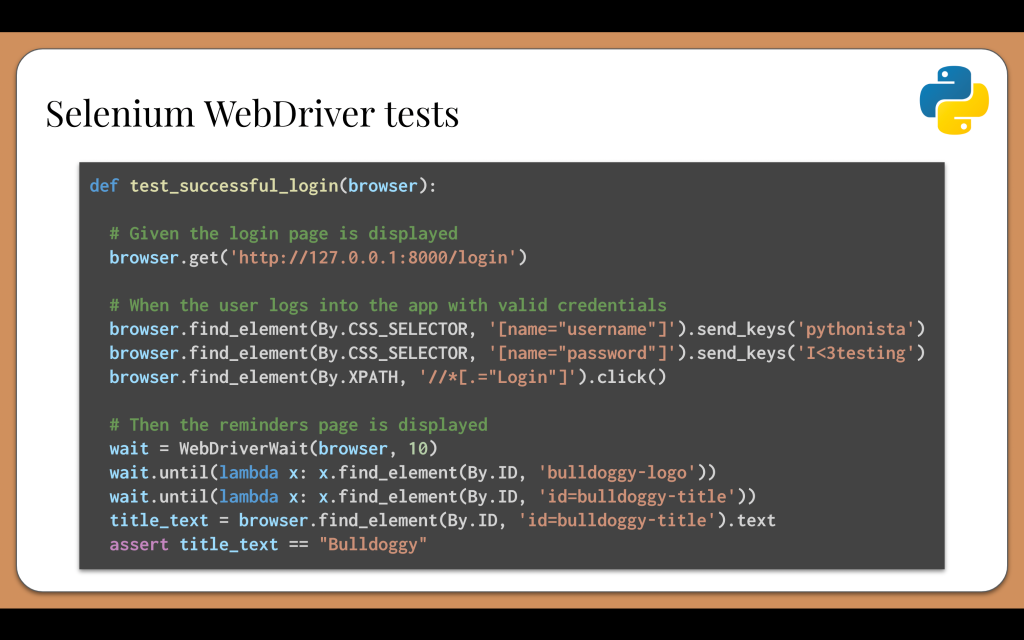

Here’s what a login test would look like when using Selenium in Python:

The test function would receive the WebDriver instance through the browser fixture we just wrote. When I write tests, I follow the Arrange-Act-Assert pattern, and I like to write my test steps using Given-When-Then language in comments.

The first step is, “Given the login page is displayed.” Here, we call “browser dot get” with the full URL for the Bulldoggy app running on the local machine.

The second step is, “When the user logs into the app with valid credentials.” This actually requires three interactions: typing the username, typing the password, and clicking the login button. For each of these, the test must first call “browser dot find element” with a locator to get the element object. They locate the username and password fields using CSS selectors based on input name, and they locate the login button using an XPath that searches for the text of the button. Once the elements are found, the test can call interactions on them like “send keys” and “click”.

Now, one thing to note is that these calls should probably use page objects or the Screenplay Pattern to make them reusable, but I chose to put raw Selenium code here to keep it basic.

The third step is, “Then the reminders page is displayed.” These lines perform assertions, but they need to wait for the reminders page to load before they can check any elements. The WebDriverWait object enables explicit waiting. With Selenium WebDriver, we need to handle waiting by ourselves, or else tests will crash when they can’t find target elements. Improper waiting is the main cause for flakiness in tests. Furthermore, implicit and explicit waits don’t mix. We must choose one or the other. Personally, I’ve found that any test project beyond a small demo needs explicit waits to be maintainable and runnable.

Selenium is great because it works well, but it does have some paint points:

- Like we just said, there is no automatic waiting. Folks often write flaky tests unintentionally because they don’t handle waiting properly. Therefore, it is strongly recommended to use a layer on top of raw Selenium like Pylenium, SeleniumBase, or a Screenplay implementation. Selenium isn’t a full test framework by itself – it is a browser automation tool that becomes part of a test framework.

- Selenium setup can be annoying. We need to install matching WebDriver executables onto the system path for every browser we test, and we need to keep their versions in sync. It’s very common to discover that tests start failing one day because a browser automatically updated its version and no longer matched its WebDriver executable. Thankfully, a new part of the Selenium project named Selenium Manager now automatically handles the executables.

- Selenium-based tests have a bad reputation for slowness. Usually, poor performance comes more from the apps under test than the tool itself, but Selenium setup and cleanup do cause a performance hit.

Cypress

Cypress is a modern frontend test framework with rich developer experience. Instead of using the WebDriver protocol, it manipulates the browser via in-browser JavaScript calls. The tests and the app operate in the same browser process. Cypress is an open source project, and the company behind it sells advanced features for it as a paid service. It can run tests on Chrome, Firefox, Edge, Electron, and WebKit (but not Safari). It also has built-in API testing support. Unfortunately, due to its design, Cypress tests must be written exclusively in JavaScript (or TypeScript).

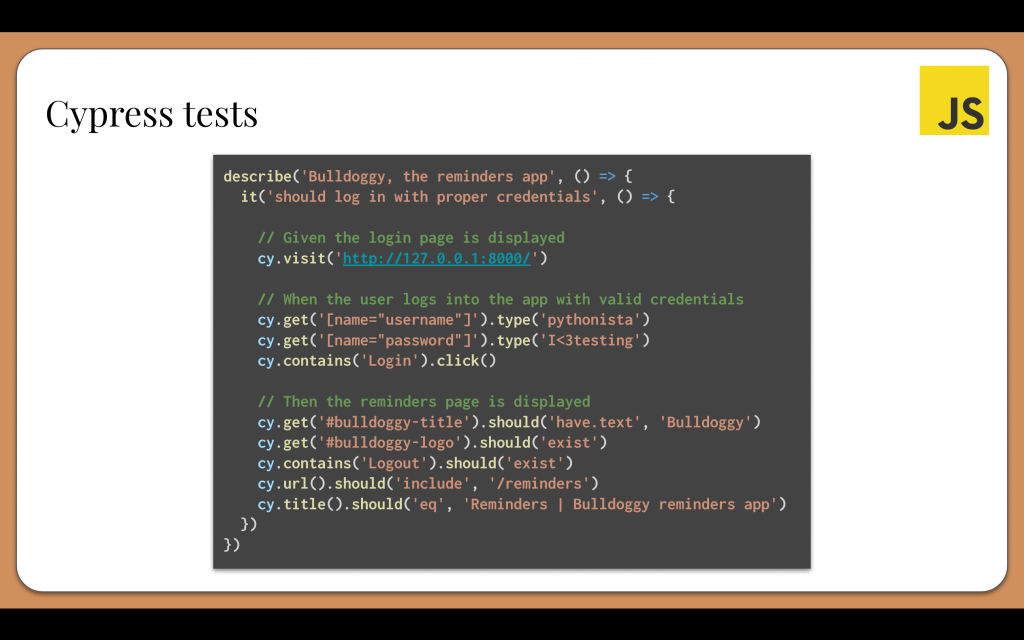

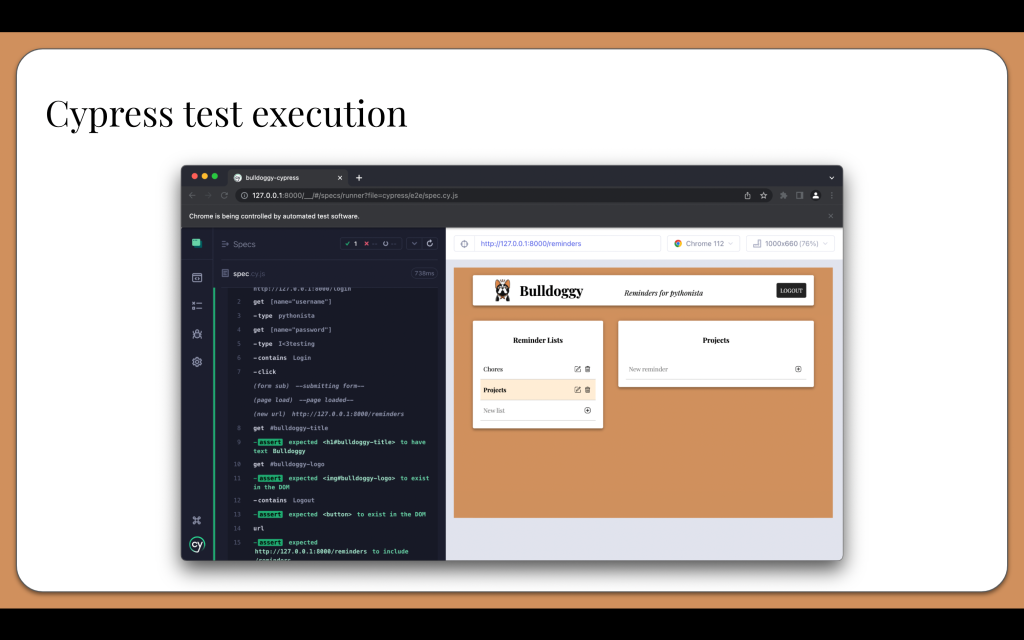

Here’s the code for the Bulldoggy login test in Cypress in JavaScript:

The steps are pretty much the same as before. Instead of creating some sort of browser object, all Cypress calls go to its cy object. The syntax is very concise and readable. We could even fit in a few more assertions. Cypress also handles waiting automatically, which makes the code less prone to flakiness.

The rich developer experience comes alive when running Cypress tests. Cypress will open a browser window that will visually execute the test in front of us. Every step is traced so we can quickly pinpoint failures. Cypress is essentially a web app that tests web apps.

While Cypress is awesome, it is JavaScript-only, which stinks for folks who use other programming languages. For example, I’m a Pythonista at heart. Would I really want to test a full-stack Python web app like Bulldoggy with a browser automation tool that doesn’t have a Python language binding? Cypress is also trapped in the browser. It has some inherent limitations, like the fact that it can’t handle more than one open tab.

Playwright

Playwright is similar to Cypress in that it’s a modern, open source test framework that is developed and maintained by a company. Playwright manipulates the browser via debug protocols, which make it the fastest of the three tools we’ve discussed today. Playwright also takes a unique approach to browsers. Instead of testing full browsers like Chrome, Firefox, and Safari, it tests the corresponding browser engines: Chromium, Firefox (Gecko), and WebKit. Like Cypress, Playwright can also test APIs, and like Selenium, Playwright offers bindings for multiple popular languages, including Python.

To set up Playwright, of course we need to install the dependency packages. Then, we need to install the browser engines. Thankfully, Playwright manages its browsers for us. All we need to do is run the appropriate “Playwright install” for the chosen language.

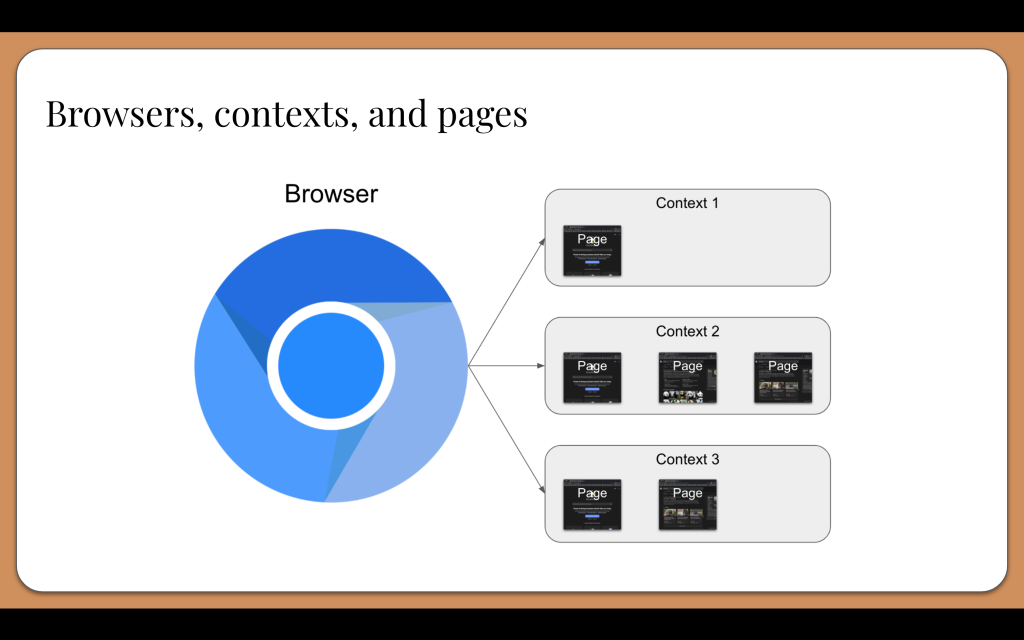

Playwright takes a unique approach to browser setup. Instead of launching a new browser instance for each test, it uses one browser instance for all tests in the suite. Each test then creates a unique browser context within the browser instance, which is like an incognito session within the browser. It is very fast to create and destroy – much faster than a full browser instance. One browser instance may simultaneously have multiple contexts. Each context keeps its own cookies and session storage, so contexts are independent of each other. Each context may also have multiple pages or tabs open at any given time. Contexts also enable scalable parallel execution. We could easily run tests in parallel with the same browser instance because each context is isolated.

Let’s see that Bulldoggy login test one more time, but this time with Playwright code in Python. Again, the code is pretty similar to what we saw before. The major differences between these browser automation tools is not so much the appearance of the code but rather how they work and perform:

With Playwright, all interactions happen with the “page” object. By default, Playwright will create:

- One browser instance to be shared by all tests in a suite

- One context for each test case

- One page within the context for each test case

When we read this code, we see locators for finding elements and methods for acting upon found elements. Notice how, like Cypress, Playwright automatically handles waiting. Playwright also packs an extensive assertion library with conditions that will wait for a reasonable timeout for their intended conditions to become true.

Again, like we said for the Selenium example code, if this were a real-world project, we would probably want to use page objects or the Screenplay Pattern to handle interactions rather than raw calls.

Playwright has a lot more cool stuff, such as the code generator and the trace viewer. However, Playwright isn’t perfect, and it also has some pain points:

- Playwright tests browser engines, not full browsers. For example, Chrome is not the same as Chromium. There might be small test gaps between the two. Your team might also need to test full browsers to satisfy compliance rules.

- Playwright is still new. It is years younger than Selenium and Cypress, so its community is smaller. You probably won’t find as many StackOverflow articles to help you as you would for the other tools. Features are also evolving rapidly, so brace yourself for changes.

Which one should you choose?

So, now that we have learned all about Selenium, Cypress, and Playwright, here’s the million-dollar question: Which one should we use? Well, the best web test tool to choose really depends on your needs. They are all great tools with pros and cons. I wanted to compare these tools head-to-head, so I created this table for quick reference:

In summary:

- Selenium WebDriver is the classic tool that historically has appealed to testers. It supports all major browsers and several programming languages. It abides by open source, standards, and governance. However, it is a low-level browser automation tool, not a full test framework. Use it with a layer on top like Serenity, Boa Constrictor, or Pylenium.

- Cypress is the darling test framework for frontend web developers. It is essentially a web app that tests web apps, and it executes tests in the same browser process as the app under test. It supports many browsers but must be coded exclusively in JavaScript. Nevertheless, its developer experience is top-notch.

- Playwright is gaining popularity very quickly for its speed and innovative optimizations. It packs all the modern features of Cypress with the multilingual support of Selenium. Although it is newer than Cypress and Selenium, it’s growing fast in terms of features and user base.

If you want to know which one I would choose, come talk with me about it! You can also watch my PyCon US 2023 talk recording to see which one I would specifically choose for my personal Python projects.