Gherkin is learned best by example. Whereas the previous post in this series focused on Gherkin syntax and semantics, this post will walk through a set of examples that show how to use all of the language parts. The examples cover basic Google searching, which is easy to explain and accessible to all. You can find other good example references from Cucumber and Behat. (Check the Automation Panda BDD page for the full table of contents.)

As a disclaimer, this post will focus entirely upon feature file examples and not upon automation through step definitions. Writing good Gherkin scenarios must come before implementing step definitions. Automation will be covered in future posts. (Note that these examples could easily be automated using Selenium.)

A Simple Feature File

Let’s start with the example from the previous post:

Feature: Google Searching As a web surfer, I want to search Google, so that I can learn new things. Scenario: Simple Google search Given a web browser is on the Google page When the search phrase "panda" is entered Then results for "panda" are shown

This is a complete feature file. It starts with a required Feature section and a description. The description is optional, and it may have as many or as few lines as desired. The description will not affect automation at all – think of it as a comment. As an Agile best practice, it should include the user story for the features under test. This feature file then has one Scenario section with a title and one each of Given–When–Then steps in order. It could have more scenarios, but for simplicity, this example has only one. Each scenario will be run independently of the other scenarios – the output of one scenario has no bearing on the next! The indents and blank lines also make the feature file easy to read.

Notice how concise yet descriptive the scenario is. Any non-technical person can easily understand how Google searches should behave from reading this scenario. “Search for pandas? Get pandas!” The feature’s behavior is clear to the developer, the tester, and the product owner. Thus, this one feature file can be shared by all stakeholders and can dispel misunderstandings.

Another thing to notice is the ability to parameterize steps. Steps should be written for reusability. A step hard-coded to search for pandas is not very reusable, but a step parameterized to search for any phrase is. Parameterization is handled at the level of the step definitions in the automation code, but by convention, it is a best practice to write parameterized values in double-quotes. This makes the parameters easy to identify.

Additional Steps

Not all behaviors can be fully described using only three steps. Thankfully, scenarios can have any number of steps using And and But. Let’s extend the previous example:

Feature: Google Searching As a web surfer, I want to search Google, so that I can learn new things. Scenario: Simple Google search Given a web browser is on the Google page When the search phrase "panda" is entered Then results for "panda" are shown And the related results include "Panda Express" But the related results do not include "pandemonium"

Now, there are three Then steps to verify the outcome. And and But steps can be attached to any type of step. They are interchangeable and do not have any unique meaning – they exist simply to make scenarios more readable. For example, the scenario above could have been written as Given-When-Then-Then-Then, but Given-When-Then-And-But makes more sense. Furthermore, And and But do not represent any sort of conditional logic. Gherkin steps are entirely sequential and do not branch based on if/else conditions.

Doc Strings

In-line parameters are not the only way to pass inputs to a step. Doc strings can pass larger pieces of text as inputs like this:

Feature: Google Searching As a web surfer, I want to search Google, so that I can learn new things. Scenario: Simple Google search Given a web browser is on the Google page When the search phrase "panda" is entered Then results for "panda" are shown And the result page displays the text """ Scientific name: Ailuropoda melanoleuca Conservation status: Endangered (Population decreasing) """

Doc strings are delimited by three double-quotes ‘”””‘. They may fit onto one line, or they may be multiple lines long. The step definition receives the doc string input as a plain old string. Gherkin doc strings are reminiscent of Python docstrings in format.

Step Tables

Tables are a valuable way to provide data with concise syntax. In Gherkin, a table can be passed into a step as an input. The example above can be rewritten to use a table for related results like this:

Feature: Google Searching As a web surfer, I want to search Google, so that I can learn new things. Scenario: Simple Google search Given a web browser is on the Google page When the search phrase "panda" is entered Then results for "panda" are shown And the following related results are shown | related | | Panda Express | | giant panda | | panda videos |

Step tables are delimited by the pipe symbol “|”. They may have as many rows or columns as desired. The first row contains column names and is not treated as input data. The table is passed into the step definition as a data structure native to the language used for automation (such as an array). Step tables may be attached to any step, but they will be connected to that step only. For good formatting, remember to indent the step table and to space the delimiters evenly.

The Background Section

Sometimes, scenarios in a feature file may share common setup steps. Rather than duplicate these steps, they can be put into a Background section:

Feature: Google Searching As a web surfer, I want to search Google, so that I can learn new things. Background: Given a web browser is on the Google page Scenario: Simple Google search for pandas When the search phrase "panda" is entered Then results for "panda" are shown Scenario: Simple Google search for elephants When the search phrase "elephant" is entered Then results for "elephant" are shown

Since each scenario is independent, the steps in the Background section will run before each scenario is run, not once for the whole set. The Background section does not have a title. It can have any type or number of steps, but as a best practice, it should be limited to Given steps.

Scenario Outlines

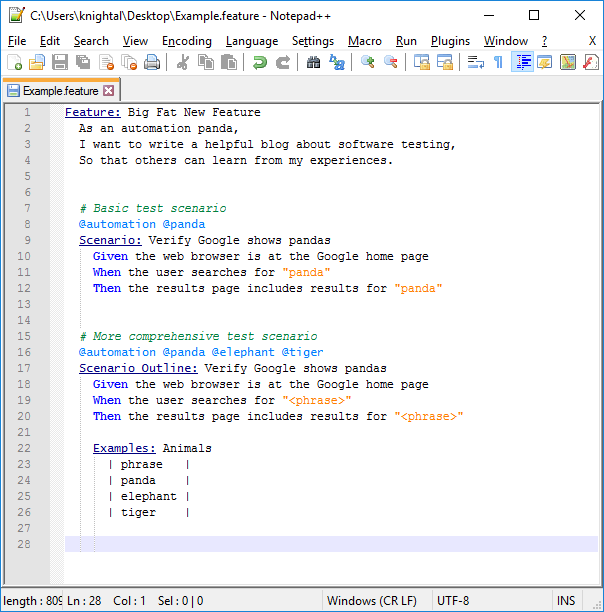

Scenario outlines bring even more reusability to Gherkin. Notice in the example above that the two scenarios are identical apart from their search terms. They could be combined with a Scenario Outline section:

Feature: Google Searching As a web surfer, I want to search Google, so that I can learn new things. Scenario Outline: Simple Google searches Given a web browser is on the Google page When the search phrase "<phrase>" is entered Then results for "<phrase>" are shown And the related results include "<related>" Examples: Animals | phrase | related | | panda | Panda Express | | elephant | Elephant Man |

Scenario outlines are parameterized using Examples tables. Each Examples table has a title and uses the same format as a step table. Each row in the table represents one test instance for that particular combination of parameters. In the example above, there would be two tests for this Scenario Outline. The table values are substituted into the steps above wherever the column name is surrounded by the “<” “>” symbols.

A Scenario Outline section may have multiple Examples tables. This may make it easier to separate combinations. For example, tables could be added for “Planets” and “Food”. Each Examples table is connected to the Scenario Outline section immediately preceding it. A feature file can have any number of Scenario Outline sections, but make sure to write them well. (See Are Multiple Scenario Outlines in a Feature File Okay?)

Be careful not to confuse step tables with Examples tables! This is a common mistake for Gherkin beginners. Step tables provide input data structures, whereas Examples tables provide input parameterization.

Tags

Tags are a great way to classify scenarios. They can be used to selectively run tests based on tag name, and they can be used to apply before-and-after wrappers around scenarios. Most BDD frameworks support tags. Any scenario can be given tags like this:

Feature: Google Searching As a web surfer, I want to search Google, so that I can learn new things. @automated @google @panda Scenario: Simple Google search Given a web browser is on the Google page When the search phrase "panda" is entered Then results for "panda" are shown

Tags start with the “@” symbol. Tag names are case-sensitive and whitespace-separated. As a best practice, they should be lowercase and use hyphens (“-“) between separate words. Tags must be put on the line before a Scenario or Scenario Outline section begins. Any number of tags may be used.

Comments

Comments allow the author to add additional information to a feature file. In Gherkin, comments must use a whole line, and each line must start with a hashtag “#”. Comment lines may appear anywhere and are ignored by the automation framework. For example:

Feature: Google Searching As a web surfer, I want to search Google, so that I can learn new things. # Test ID: 12345 # Author: Andy Scenario: Simple Google search Given a web browser is on the Google page When the search phrase "panda" is entered Then results for "panda" are shown

Since Gherkin is very self-documenting, it is a best practice to limit the use of comments in favor of more descriptive steps and titles.

Writing Good Gherkin

This post merely shows how to use the Gherkin syntax. The next post will cover how to write good Gherkin feature files.