Karate is a relatively new open source framework for testing Web services. Even though Karate is written in Java, its main value proposition is that testers don’t need to do any Java programming in order to write fully automated tests. Instead, testers use a Gherkin-like language with steps for making requests and validating responses. It’s like Cucumber with out-of-the-box Web API steps! There are a bunch of other nifty features, too.

This article is my quick-start guide for Karate. As a prerequisite, make sure you understand how Web services work (like REST APIs). Knowing BDD will also help.

My System

Since Karate is an open-source Java project, it can run almost anywhere. Here’s my system config:

- macOS 10.13.6 (High Sierra)

- Java 1.8.0_191

- Apache Maven 3.6.0

- Karate 0.9.0

Warning: I initially attempted to run my Karate project using Java 11.0.1, but I repeatedly hit SSL handshake exceptions despite trying many fixes. Downgrading to Java 8 fixed the errors. See Issue #617.

Project Setup

I created my Karate project using the Maven archetype since I am quite familiar with Maven. I named my project “firstchop”:

mvn archetype:generate \ -DarchetypeGroupId=com.intuit.karate \ -DarchetypeArtifactId=karate-archetype \ -DarchetypeVersion=0.9.0 \ -DgroupId=com.automationpanda \ -DartifactId=firstchop

The directory layout was standard for Java Maven / Cucumber-JVM projects. (In fact, Karate was based on Cucumber-JVM until version 0.8.0.) Interestingly, the Karate docs recommend placing feature files under src/test/java instead of src/test/resources.

IDE

The Karate docs recommend using Eclipse or IntelliJ IDEA for developing Karate tests. Both IDEs offer support for JUnit and Cucumber, which Karate can leverage not only for editing but also for running tests. I’d probably use IntelliJ IDEA for serious testing.

However, for my initial exploration, I chose to use Visual Studio Code. Why?

- It’s fast and easy.

- It has good support for Java and Gherkin.

- It has a file explorer and an integrated terminal.

Here’s what my Karate project looked like inside Visual Studio Code. Nice!

The Examples

The archetype project included example tests in the users.feature file. The first scenario from the file, copied below, tests getting users from the JSONPlaceholder REST API:

Feature: sample karate test script Background: * url 'https://jsonplaceholder.typicode.com' Scenario: get all users and then get the first user by id Given path 'users' When method get Then status 200 * def first = response[0] Given path 'users', first.id When method get Then status 200

Anyone familiar with Cucumber will immediately recognize the Given/When/Then format for scenarios. However, Karate’s standard steps make the language more powerful than raw Gherkin:

- Given steps build requests

- When steps make request calls

- Then steps validate responses

- Catch-all steps (*) provide additional directives, like setting variables

All steps are quite concise. The Java implementation is essentially hidden from the tester (unless, of course, they want to plunge into the framework’s lower levels). Furthermore, this scenario shows how to use data from one response as the input for a second request.

Running Tests

Since I chose to use Maven and Visual Studio Code, the easiest way to run tests without any additional configuration was through the command line using “mvn test”. The example tests came with an ExamplesTest.java file that will run all feature files in the package when it is discovered during Maven’s “test” phase. The project defaulted to using JUnit 4, but JUnit 5 is also supported.

Running the tests will print many lines to the console. Every request and response will be printed. Below is the tail end of a successful run for users.feature:

$ mvn test . . . --------------------------------------------------------- feature: classpath:examples/users/users.feature scenarios: 2 | passed: 2 | failed: 0 | time: 1.5232 --------------------------------------------------------- HTML report: (paste into browser to view) | Karate version: 0.9.0 file:/path/to/firstchop/target/surefire-reports/examples.users.users.html --------------------------------------------------------- Tests run: 2, Failures: 0, Errors: 0, Skipped: 0, Time elapsed: 3.09 sec Results : Tests run: 2, Failures: 0, Errors: 0, Skipped: 0 [INFO] ------------------------------------------------------------------------ [INFO] BUILD SUCCESS [INFO] ------------------------------------------------------------------------ [INFO] Total time: 5.635 s [INFO] Finished at: 2018-12-09T23:32:29-05:00 [INFO] ------------------------------------------------------------------------

Karate can generate helpful test reports, too. The project generates JUnit reports by default, but other report formats like Cucumber reports are also possible.

The JUnit HTML report shows a step-by-step log for each scenario.

Full requests and responses are automatically logged, which is great for debugging.

Failures are visually easy to identify. Above, I hacked the example to deliberately fail.

My Scenarios

Seeing examples is great, but I wanted to write my own scenarios with a real Web service for some hands-on experience. So, I wrote a test for Recipe Puppy, a search engine that provides links to recipes for input ingredients:

Feature: Recipe Puppy

Background:

* url 'http://www.recipepuppy.com'

Scenario Outline: Get a recipe for <ingredient>

Given path 'api'

And params {i: '<ingredient>'}

When method get

Then status 200

And match response contains {results: '#array'}

And match response.results[*] contains

"""

{

title: '#string',

href: '#string',

ingredients: '#regex <ingredient>',

thumbnail: '#string'

}

"""

Examples:

| ingredient |

| tomato |

| pepperoni |

| cheese |

Here are a few things I learned while writing this new feature file:

- Scenario Outlines are supported, but data-driven features are preferred.

- JSON objects can be used as step arguments or as variables.

- Matching syntax is simple but sophisticated.

- Markers like “#array” support fuzzy matching when specific values are unknown.

- Multi-line JSON expressions need block quotes.

This new scenario ran just as successfully as the examples!

Standalone Execution

Even though writing tests using Karate’s domain-specific language does not require Java development skills, setting up the full Karate project does. Thankfully, Karate provides a standalone JAR that can run feature files without any other dependencies or configuration. It simply takes in paths to feature files, runs them, and generates Cucumber reports. The standalone JAR would be a good option for testers who don’t have strong programming skills.

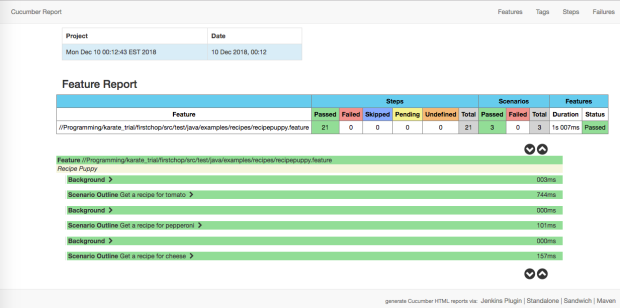

This was the Cucumber report generated by running my Recipe Puppy test with the standalone JAR.

Other Features

Despite being a fairly young project (with a GitHub creation date of February 7, 2017), Karate is full of nifty features that I have yet to try:

- Parallel test execution

- A mock servlet

- A UI for visually debugging scripts

- Reading files of many types into variables

- Calling a feature file from another feature file

- Calling JavaScript code

- Calling Java code

- Using scenarios as Gatling performance tests

Project contributors are also experimenting to extend Karate to test browser, mobile, and desktop UIs using Selenium WebDriver.

Analysis

Overall, Karate is a great tool for testing Web services. It handles all of the programming implementation details so that testers can focus more on testing. Its syntax is concise, clear, and versatile. Its native support for JSON object makes request and response handling feel natural. The GitHub docs are on-point. Anyone testing REST APIs should give it serious consideration.

Even though Karate uses Gherkin-like syntax, it is not truly a behavior-driven test framework. Instead, it simply leverages the strengths of Cucumber – readability, reusability, and tooling – to make automated Web service testing easier. I have long stated that one of the best solutions to test automation challenges is to create a domain-specific testing language that automatically handles low-level details. (See Behavior-Driven Blasphemy.) The Karate project validates my claim. Karate’s DSL acts much more like a testing language than a business-oriented specification language. Its Gherkin keywords simply provide structure and familiarity to its steps. And it’s perfectly okay that Karate isn’t “pure BDD” – just ask the project’s creator.

With that said, I would argue that a tester probably needs basic programming skills to be successful with Karate. Execution needs Java setup no matter what, and feature files are really just fancy test scripts. And Web service APIs are inherently code-y.

I look forward to seeing how the Karate project grows, especially if/when WebDriver-based steps are added to the language.

Resources

- The Karate GitHub project

- REST API Testing with Karate (Baeldung)

- Karate a Rest Test Tool – Basic API Testing (Joe Colantonio)

- Karate framework: REST API testing made easy! (Mohammed Aboullaite)