JetBrains PyCharm is one of the best Python IDEs around. It’s smooth and intuitive – a big step up from Atom or Notepad++ for big projects. PyCharm is available as a standalone IDE or as a plugin for its big sister, IntelliJ IDEA. The free Community Edition provides basic features akin to IntelliJ, while the licensed Professional Edition provides advanced features such as web development and database tools. The Professional Edition isn’t cheap, though: a license for one user may cost up to $199 annually (though discounts and free licenses may be available).

This guide shows how to develop Django web projects using PyCharm Community Edition. Even though Django-specific features are available only in PyCharm Professional Edition, it is still possible to develop Django projects using the free version with help from the command line. Personally, I’ve been using the free version of PyCharm to develop a small web site for a side business of mine. This guide covers setup steps, basic actions, and feature limitations based on my own experiences. Due to the limitations in the free version, I recommend it only for small Django projects or for hobbyists who want to play around. I also recommend considering Visual Studio Code as an alternative, as shown in my article Django Projects in Visual Studio Code.

Prerequisites

This guide focuses specifically on configuring PyCharm Community Edition for Django development. As such, readers should be familiar with Python and the Django web framework. Readers should also be comfortable with the command line for a few actions, specifically for Django admin commands. Experience with JetBrains software like PyCharm and IntelliJ IDEA is helpful but not required.

Python and PyCharm Community Edition must be installed on the development machine. If you are not sure which version of Python to use, I strongly recommend Python 3. Any required Python packages (namely Django) should be installed via pip.

Creating Django Projects and Apps

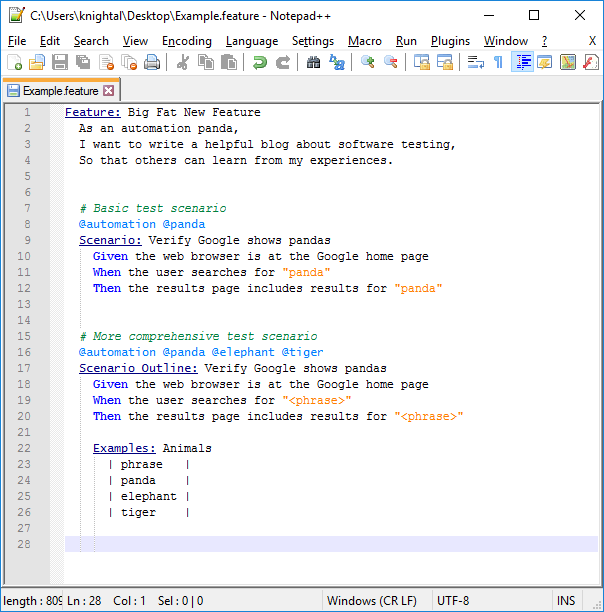

Django projects and apps require a specific directory layout with some required settings. It is possible to create this content manually through PyCharm, but it is recommended to use the standard Django commands instead, as shown in Part 1 of the official Django tutorial.

> django-admin startproject newproject > cd newproject > django-admin startapp newapp

Then, open the new project in PyCharm. The files and directories will be visible in the Project Explorer view.

The project root directory should be at the top of Project Explorer. The .idea folder contains IDE-specific config files that are not relevant for Django.

Creating New Files and Directories

Creating new files and directories is easy. Simply right-click the parent directory in Project Explorer and select the appropriate file type under New. Files may be deleted using right-click options as well or by highlighting the file and typing the Delete or Backspace key.

Files and folders are easy to visually create, copy, move, rename, and delete.

Django projects require a specific directory structure. Make sure to put files in the right places with the correct names. PyCharm Community Edition won’t check for you.

Writing New Code

Double-click any file in Project Explorer to open it in an editor. The Python editor offers all standard IDE features like source highlighting, real-time error checking, code completion, and code navigation. This is the main reason why I use PyCharm over a simpler editor for Python development. PyCharm also has many keyboard shortcuts to make actions easier.

Nice.

Editors for other file types, such as HTML, CSS, or JavaScript, may require additional plugins not included with PyCharm Community Edition. For example, Django templates must be edited in the regular HTML editor because the special editor is available only in the Professional Edition.

Workable, but not as nice.

Running Commands from the Command Line

Django admin commands can be run from the command line. PyCharm automatically refreshes any file changes almost immediately. Typically, I switch to the command line to add new apps, make migrations, and update translations. I also created a few aliases for easier file searching.

> python manage.py makemigrations > python manage.py migrate > python manage.py makemessages -l zh > python manage.py compilemessages > python manage.py test > python manage.py collectstatic > python manage.py runserver

Creating Run Configurations

PyCharm Community Edition does not include the Django manage.py utility feature. Nevertheless, it is possible to create Run Configurations for any Django admin command so that they can be run in the IDE instead of at the command line.

First, make sure that a Project SDK is set. From the File menu, select Project Structure…. Verify that a Project SDK is assigned on the Project tab. If not, then you may need to create a new one – the SDK should be the Python installation directory or a virtual environment. Make sure to save the new Project SDK setting by clicking the OK button.

Don’t leave that Project SDK blank!

Then from the Run menu, select Edit Configurations…. Click the plus button in the upper-left corner to add a Python configuration. Give the config a good name (like “Django: <command>”). Then, set Script to “manage.py” and Script parameters to the name and options for the desired Django admin command (like “runserver”). Set Working directory to the absolute path of the project root directory. Make sure the appropriate Python SDK is selected and the PYTHONPATH settings are checked. Click the OK button to save the config. The command can then be run from Run menu options or from the run buttons in the upper-right corner of the IDE window.

Run configurations should look like this. Anything done at the command line can also be done here.

When commands are run, the Run view appears at the bottom of the IDE window to show console output.

Special run configurations are particularly useful for the “test” and “runserver” commands because they enable rudimentary debugging. You can set breakpoints, run the command with debugging, and step through the Python code. If you need to interact with a web page to exercise the code, PyCharm will take screen focus once a breakpoint is hit. Even though debugging Django templates is not possible in the free version, debugging the Python code can help identify most problems. Be warned that debugging is typically a bit slower than normal execution.

Debugging makes Django development so much easier.

I typically use the command line instead of run configurations for other Django commands just for simplicity.

Version Control Systems

PyCharm has out-of-the-box support for version control systems like Git and Subversion. VCS actions are available under the VCS menu or when right-clicking a file in Project Explorer. PyCharm can directly check out projects from a repository, add new projects to a repository, or automatically identify the version control system being used when opening a project. Any VCS commands entered at the command line will be automatically reflected in PyCharm.

PyCharm’s VCS menu is initially generic. Once you select a VCS for your project, the options will be changed to reflect the chosen VCS. For example, Git will have options for “Fetch”, “Pull”, and “Push”.

Personally, I use Git with either GitHub or Atlassian Bitbucket. I prefer to do most Git actions like graphically through PyCharm, but occasionally I drop to the command line when I need to do more advanced operations (like checking commit IDs or forcing hard resets). PyCharm also has support for .gitignore files.

Python Virtual Environments

Creating virtual environments is a great way to manage Python project dependencies. Virtual environments are especially useful when deploying Django web apps. I strongly recommend setting up a virtual environment for every Python project you develop.

PyCharm can use virtual environments to run the project. If a virtual environment already exists, then it can be set as the Project SDK under Project Structure as described above. Select New… > Python SDK > Add Local, and set the path. Otherwise, new virtual environments can be created directly through PyCharm. Follow the same process to add a virtual environment, but under Python SDK, select Create VirtualEnv instead of Add Local. Give the new virtual environment an appropriate name and path. Typically, I put my virtual environments either all in one common place or one level up from my project root directory.

Creating a new virtual environment is pretty painless.

Databases

Out of the box, PyCharm Community Edition won’t give you database tools. You’re stuck with third-party plugins, the command line, or external database tools. This isn’t terrible, though. Since Django abstracts data into the Model layer, most developers rarely need to directly interact with the underlying database. Nevertheless, the open-source Database Navigator plugin provides support in PyCharm for the major databases (Oracle, MySQL, SQLite, PostgreSQL).

Limitations

The sections above show that PyCharm Community Edition can handle Django projects just like any other Python projects. This is a blessing and a curse, because advanced features are available only in the Professional Edition:

- Django template support

- Inter-project navigation (view to template)

- Better code completion

- Identifier resolution (especially class-to-instance fields)

- Model dependency graphs

- manage.py utility console

- Database tools

The two features that matter most to me are the template support and the better code completion. With templates, I sometimes make typos or forget closing tags. With code completion, not all options are available because Django does some interesting things with model fields and dynamically-added attributes. However, all these missing features are “nice-to-have” but not “need-to-have” for me.

Conclusion

I hope you found this guide useful! Feel free to enter suggestions for better usage in the comments section below. You may also want to look at alternatives, such as Visual Studio Code or PyDev.